see also: TA (throughput accounting) and TDABC (time driven activity based costing)…the fabric, the ‘warp and woof’ of healthcare accounting?

Throughput Accounting— a natural for Hospitals?

In my work with increasing OR productivity, throughput accounting quickly shows the benefits of a change in approach or strategy. It’s seems a natural link between systems engineering (lean, six sigma, etc) and healthcare facility finance. Does anyone else use it?

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Throughput Accounting (TA) is a principle-based and comprehensive management accounting approach that provides managers with decision support information for enterprise profitability…

1 month ago

Wayne Fischer • …and then there’s the claim from Michael Porter and Robert Kaplan that *they* have the Holy Grail of healthcare cost accounting: “time-driven activity-based costing.” [“How to solve the cost crisis in health care,” Harvard Business Review, SepOct 2011, pp 47-64 ]

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Wayne- They’re different in what they measure, how they group, how they integrate with other things, and ease of use. Have a close look.

Porter and Kaplan are on the right track, but they’re not the cutting edge and seem to be picking up ideas that have been circulating for a bit.

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Hmmm…Sometimes I’m dense.

Wayne Fischer • My point being, there are a *lot* of “experts” running around with the cure for healthcare – all different (present company excepted, of course)… 🙂

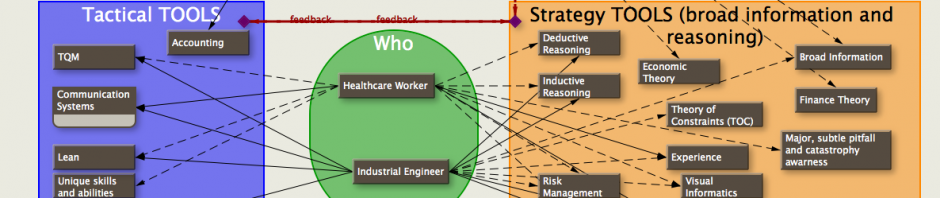

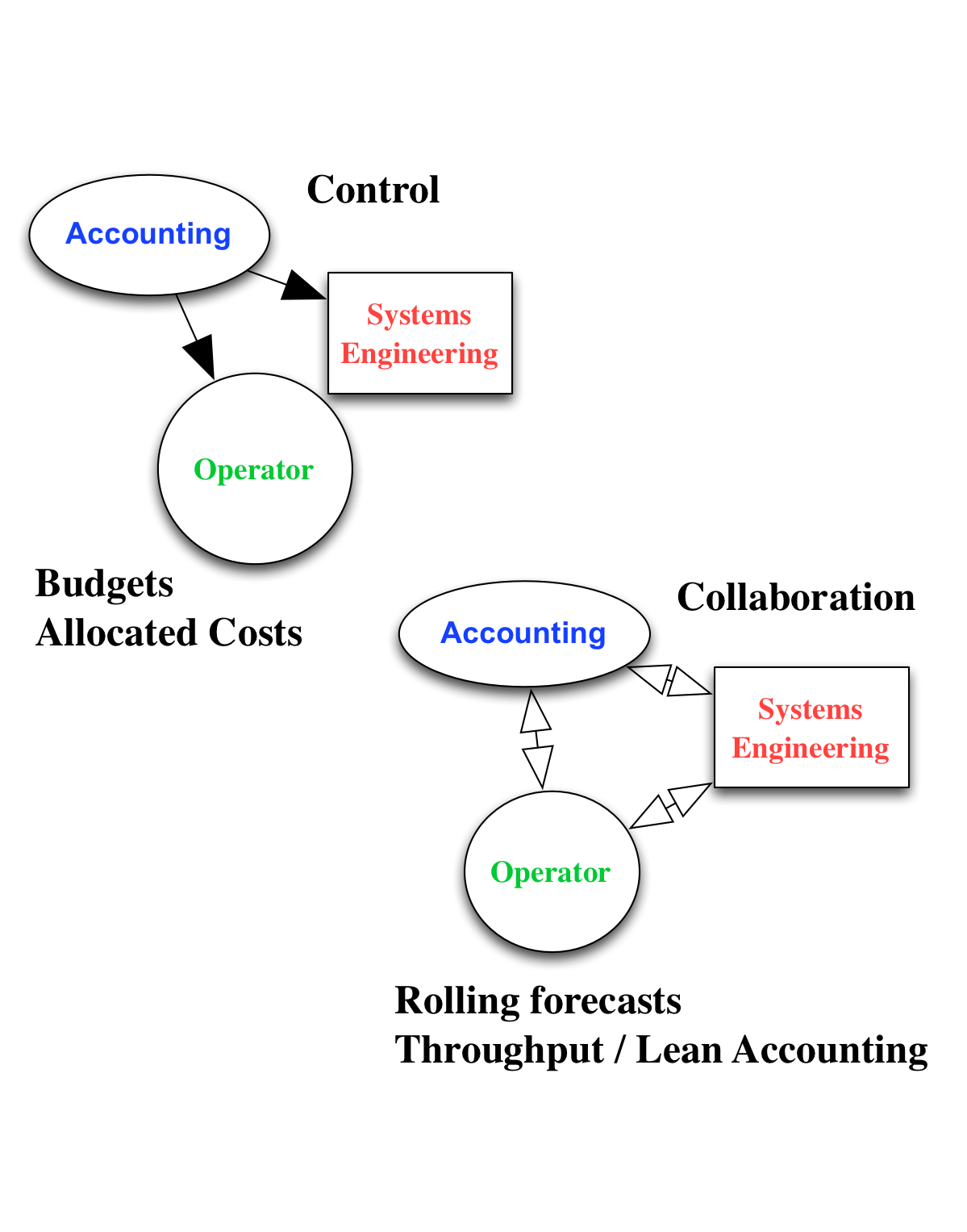

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • I like to think in terms of tools. Normal cost accounting was a KISS tool for what it was designed—piecemeal work. It is a very difficult tool to (inappropriately) try to use in a complicated system of many people with different goals and processes interacting together. Good way to get bizarre results and have the accounting tail wag the process dog.

Throughput accounting is a KISS tool for a healthcare type system. Dog wags tail. No cure all, just a better tool to bring systems engineers and administration into sync.

Wayne Fischer • Here’s my idea: Since UT M.D. Anderson Cancer Center is already testing the Porter / Kaplan TDABC method, and it makes sense, when I get started on my six-month pilot using Statit (see the demo videos athttp://www.statit.com/healthcare.shtml), I’ll set up both sets of metrics (TDABC and ToC Throughput Accounting) for a true test – comparing decisions and results… 🙂

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Hmmm… Let me know when you start setting it up. It’d be interesting to see comparisons of ease of use, cohesive action among all parties, and what parameters you’d use for financial end results (not to mention risk and other results).

I can’t imaging how’d you could do both in the same facility. Maybe you’d need one department/facility using TDABC, and a separate department/facility using TOC.

Confound it…could be tough. But then you like a challenge. 🙂

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Thanks for the Statit link. I’ve a friend who does OPPE for hospitals; I’ll pass it along.

Perusing the sight, though, I already can invasion several ways to game (come up with erroneous data) the system to make certain people look better than others.

Wayne Fischer • Right: difficult for sure. And a-yepper, would like to set it up as TDABC in one unit / department, TPA in another. But barring that, I could just document both sets of metrics’ values over time, what decisions *should* have been made based on those metrics, what decisions *were* made, and the results. Not a very satisfying way to go – but it would be a start…

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • I’d help you with the TPA side (and implementation of TOC in the department if needed). It would have been easier if I was with SWIFT at the TMC VA, it’d be right around the corner. But heh…the government works in mysterious ways.

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Ahhh…What would we do without Wikipedia! Here’s a brief synopsis of various “Cost Accounting” systems: Standard, Lean, Activity-based, Resource Consumption, Throughput, and Marginal:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cost_accounting#Activity-based_costing

and some comparisons between ABC and Throughput accounting:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Activity-based_costing

I’d also like to add ”Real Option Accounting”, but real options could probably be more effectively dealt with outside the realm of accounting as can much of the decision making in Throughput accounting. In fact, that could be a significant virtue: not letting one try to use the wrong tool for the job.

Different branches of mathematics are often better at dealing with specific problems, and sometimes only one branch can actually solve the problem.

Too bad accounting systems don’t come with safety switches that prevent them from being used dangerously.

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Form follows function… Accounting follows process?

Stuart Singer • Brian / Wayne,

Does HFMA have any opinions on either of these methodologies? Are there any journal articles you’ve come across re: hospitals that are using TPA with the benefits they’ve found from using it?

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Robert- If I remember correctly, Steven Bragg was not very complementary about ABC in his book. I agree that TPA would be better.

It should also be possible to compare the different accounting system reports to ‘reality’ and wise decision making with the goal to eventually stop using the misleading accounting systems. Who knows?—maybe different accounting systems will work better in different departments.

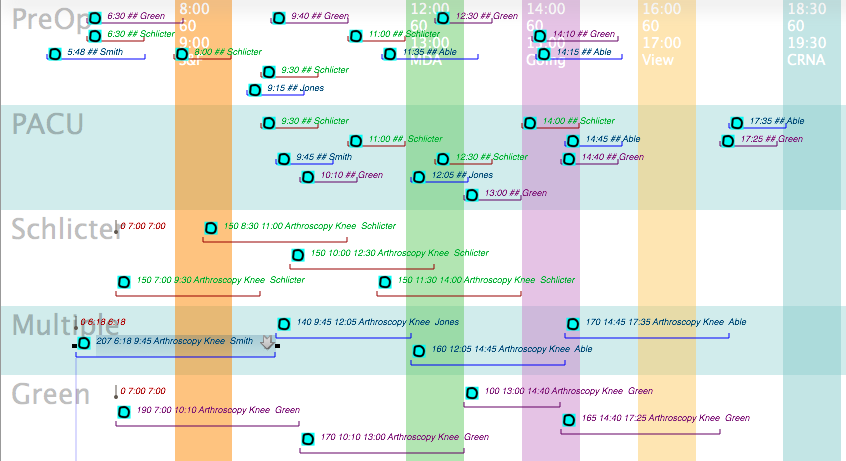

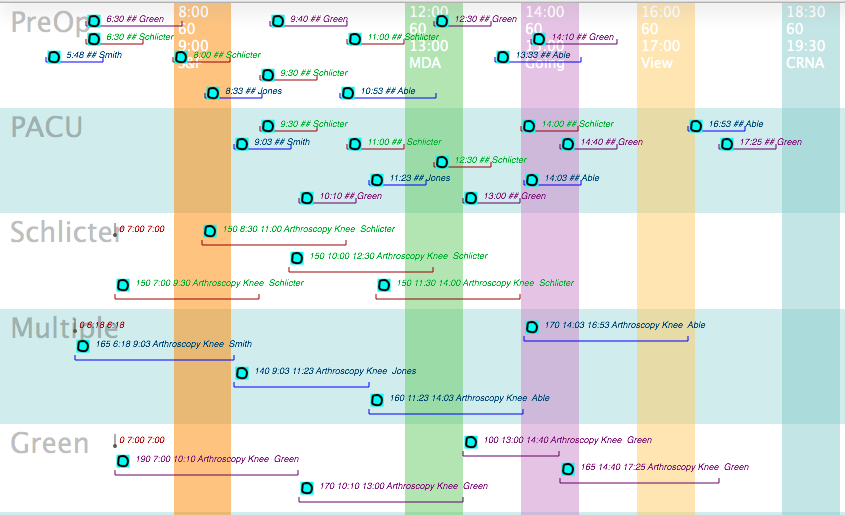

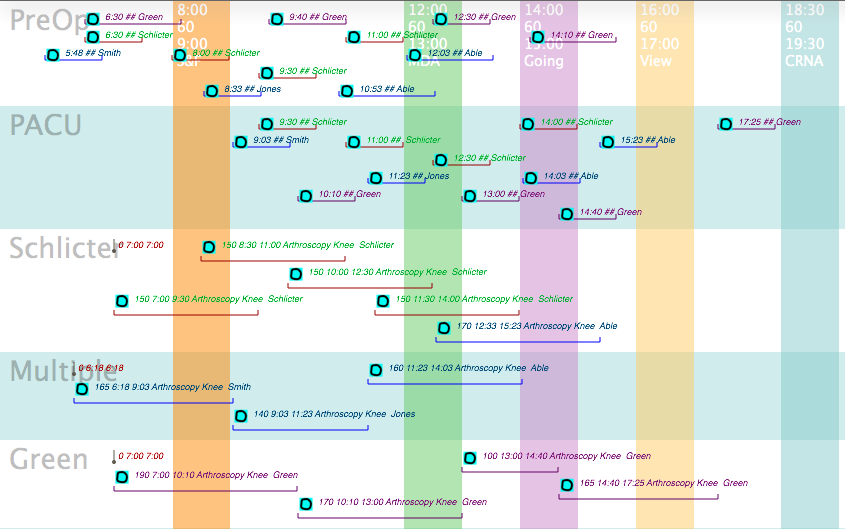

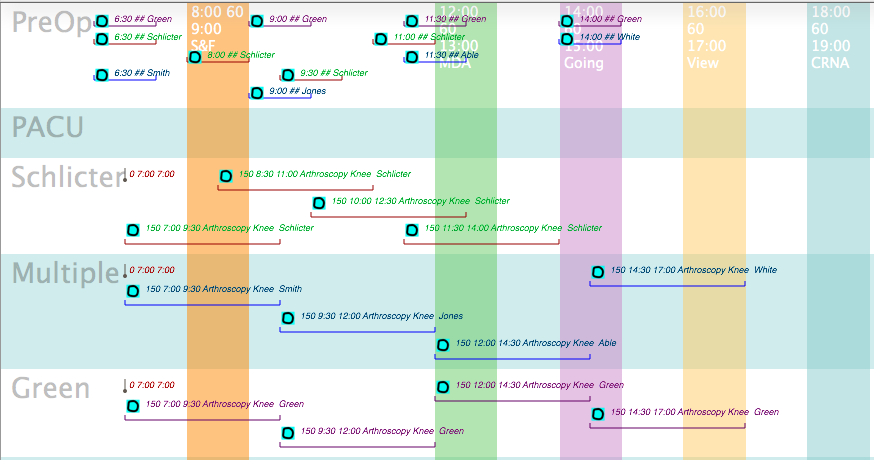

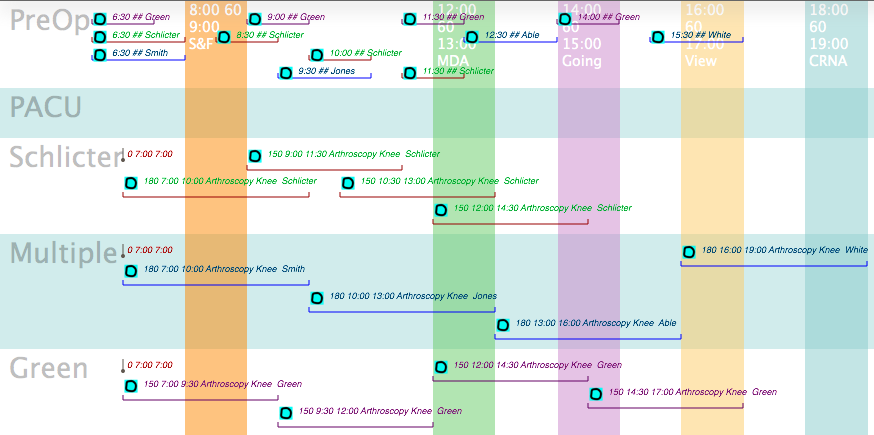

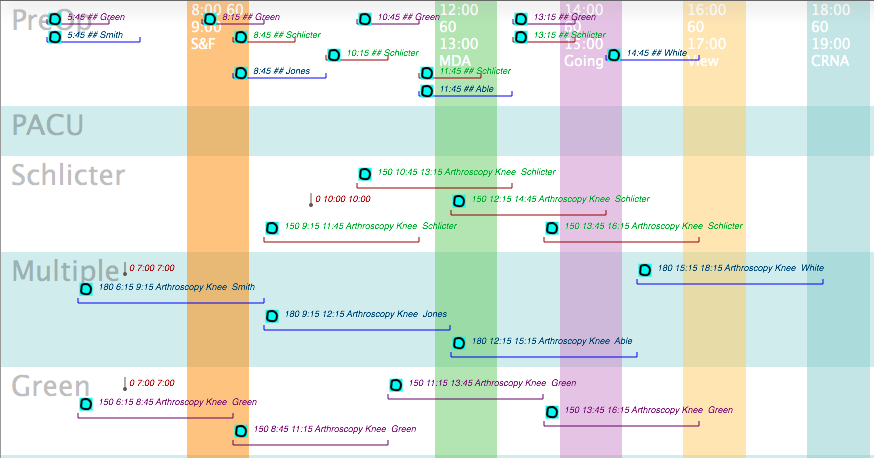

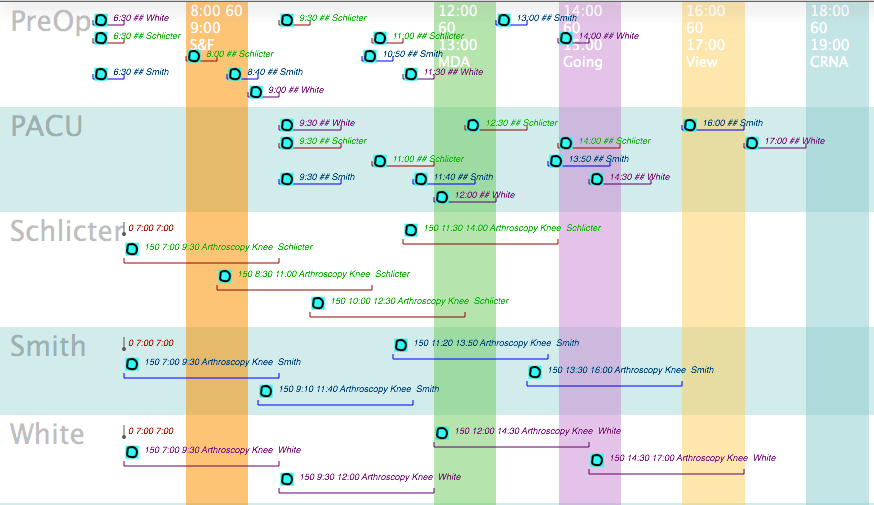

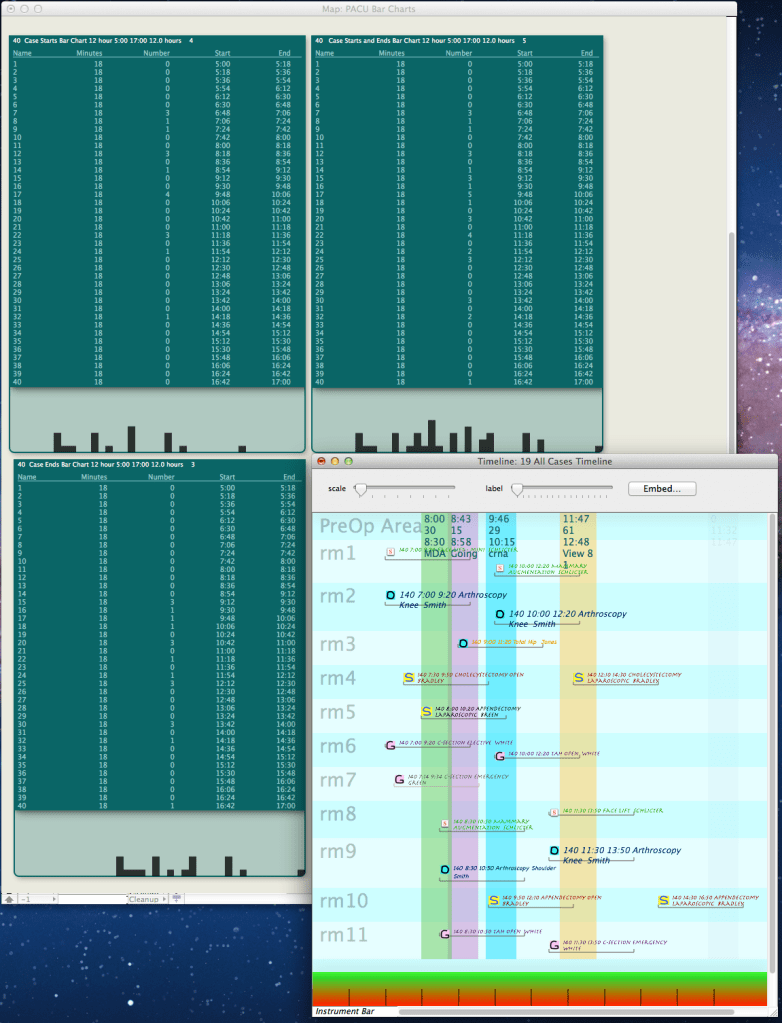

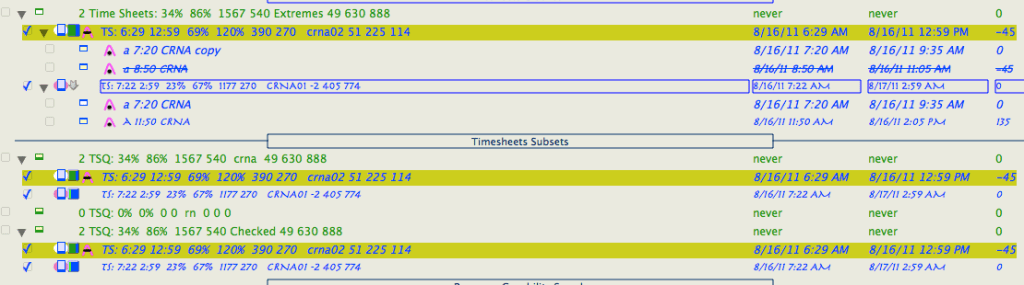

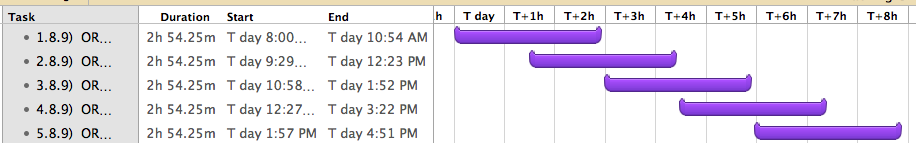

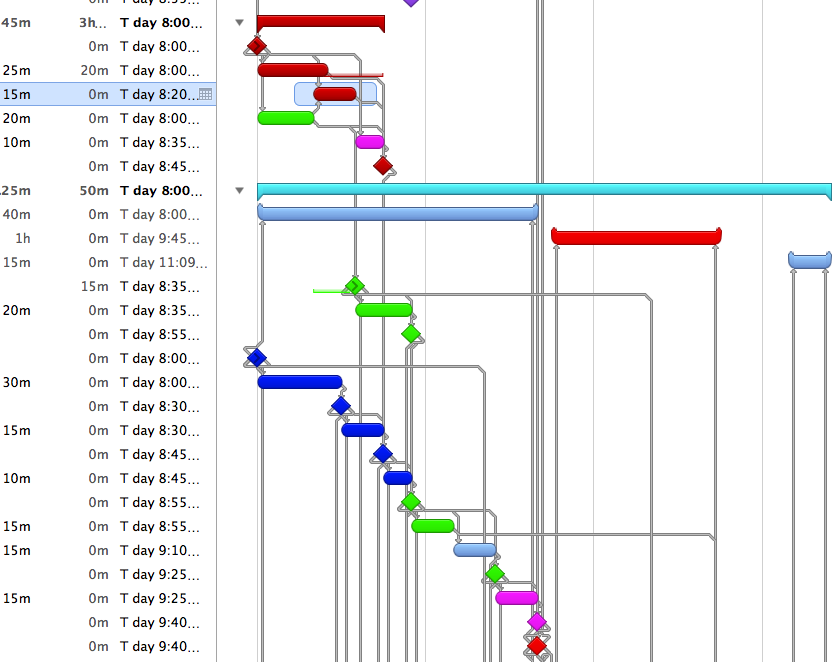

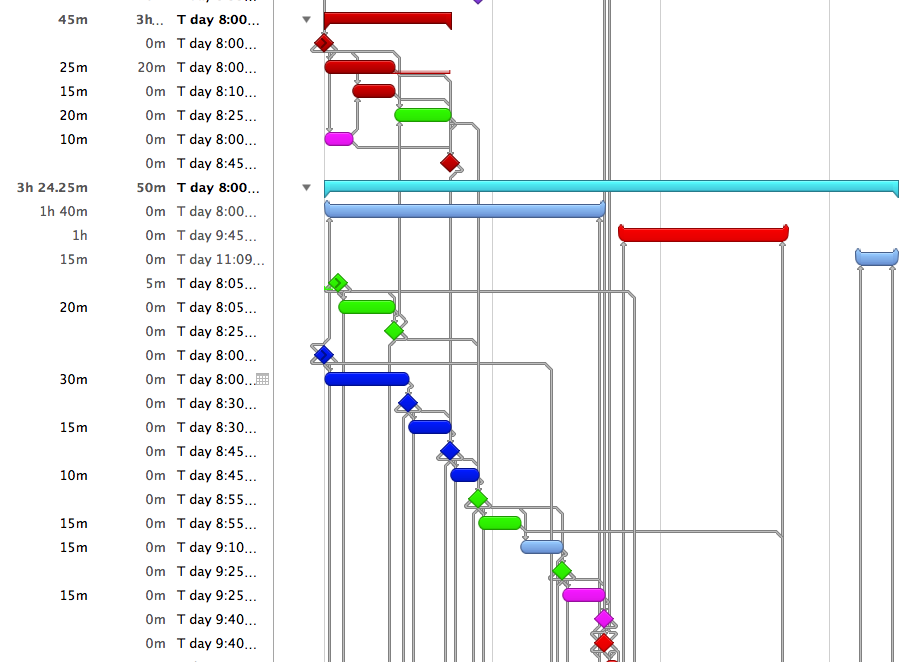

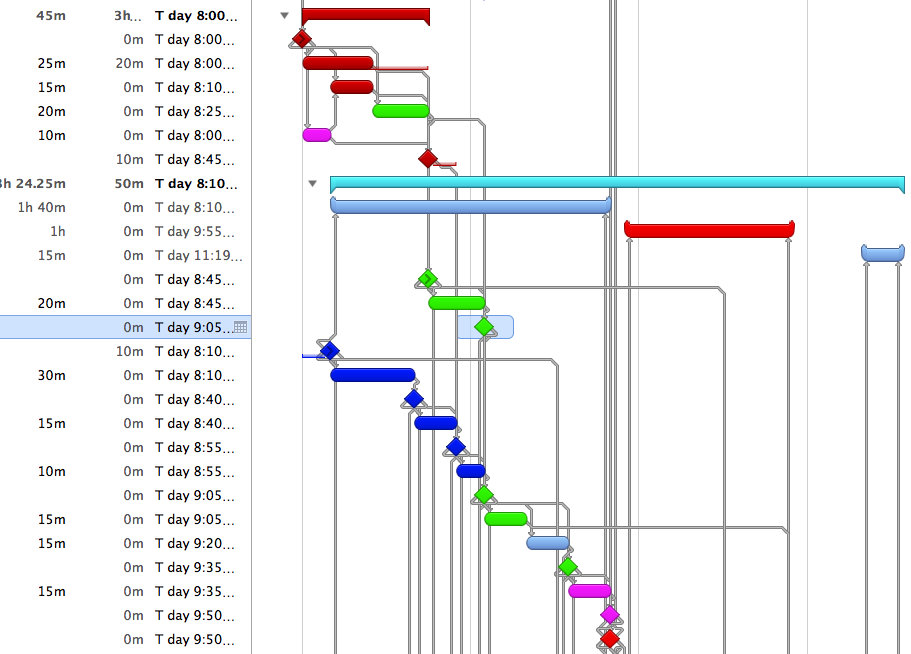

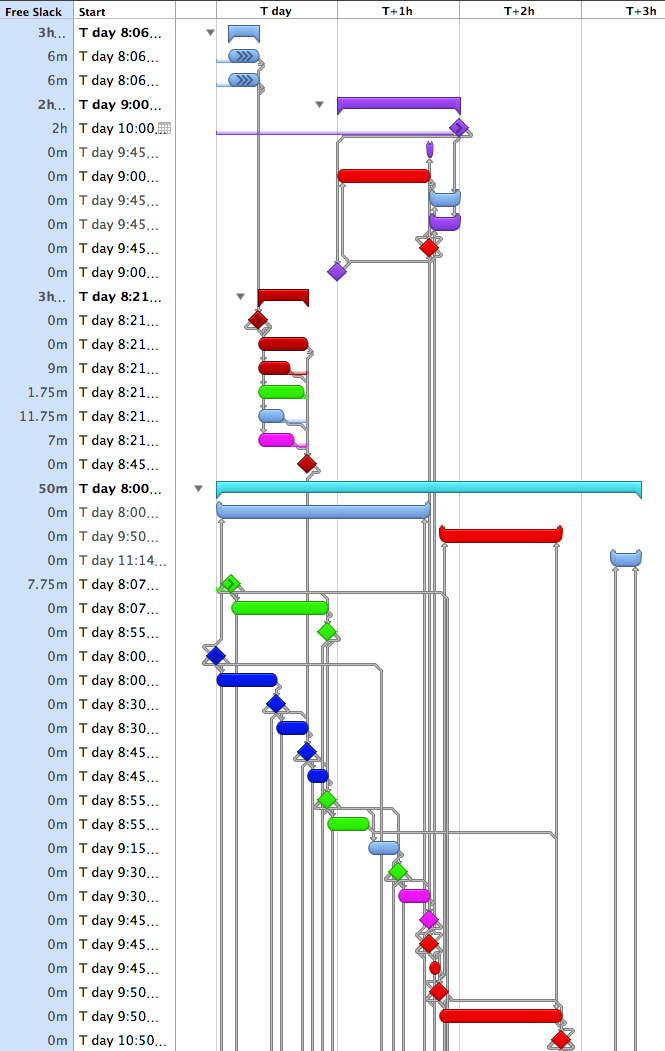

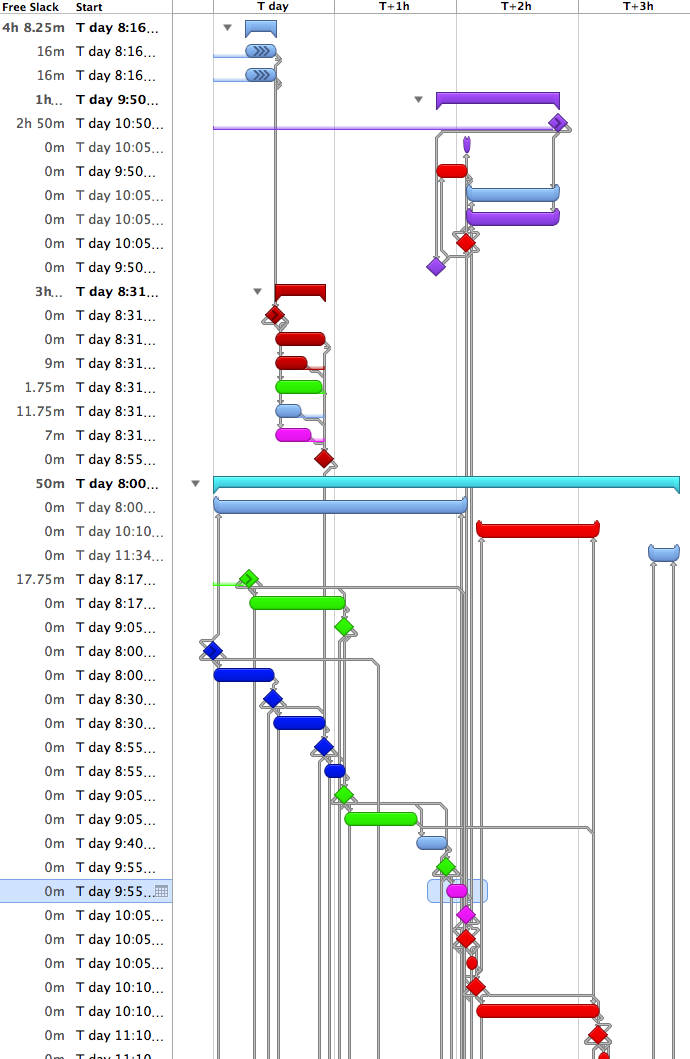

I’ve modified my accounting software (great company-versatile software) to collect accounting data in the standard cost accounting manner, yet give reports in a Throughput Accounting or Activity-based Accounting to see which correlates best on a daily basis with the decisions that would be made by systems engineers working on process improvement.

The CFO can look at daily reports and see the effects of non-efficient scheduling vs lean scheduling vs throughput scheduling (TOC) in the OR (and elsewhere), and which accounting system complements the process improvements.

I suspect that it would take the accounting department a while to become accustomed to viewing the different groupings of their costs and revenue, but the systems engineers should be able to intuitively understand and use the reports for their own feedback.

Wayne Fischer • OK, Brain, I’ll bite: What is the “great company – versatile software?”

Stuart: What is “HFMA?”

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Wayne : No need to bite…Just some good, inexpensive (relatively), commercially available accounting software (there are probably others) that lets you add/modify fields for all records, do very specific queries, groupings,and reports and lets you export every bit of data to external programs for analysis if needed.

The program’s strength is in letting you collect and modify the data that you need in an efficient manner without needing a department full of accountants. This makes for very fast analysis and modifications to fit your company. Of course, if you don’t know what to collect or how to set it up and analyze the data, then it’s no better that QuickBooks.

But isn’t that often the situation—It’s not just what you have, but how you use it…

Douglas Zech • Brian,

You continue to impress me with your ability to see structural weaknesses and find solutions. Either lean accounting or TOC accounting would be a much better system. When I worked in industry all companies had moved away from traditional GAAP cost accounting to methods more focused on cash flow.

GAAP was developed in the 1890’s and really hasn’t changed much. Yet we still run entities based on how GAAP accounting affects our P&L’s and balance sheets. There’s an old joke- why did the accountant cross the road?……. Because that’s the way they did it last year. So true, I’ve found.

In my less than two years in a hospital setting I’ve found multiple instance where we’ve reduced waste (traditional lean 7 wastes), but Finance has said this is bad. For example, cutting throughput time for a patient almost in half (good in lean terms- less waiting waste) became “lowered productivity” due to lower census volumes when finance got ahold of the results (bad in GAAP terms as costs are allocated over less patient care hours). The same with “room utilization.” Faster throughput means more downtime for expensive procedure rooms, which finance abhors; even though we’re making the same amount of money and have additional capacity.

What seems obvious to me evidently isn’t so obvious. It’s refreshing to see others highlighting the same issues. They say “what gets measured gets done” but we need to move further as to what specifically is being measured, as it is driving behaviors.

When I was young I was a Big 5 auditor/CPA/CMA (hey- I needed the money!). I realized fast that wasn’t for me, as they were driving the wrong behaviors due to GAAP requirements and other regulations. It’s still the same, I guess.

Wayne Fischer • Nice sidestep, Brian – still waiting to hear the name of the software…

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Ahh, Wayne… It takes me years to find good software. I can’t just tell you 🙂

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Douglas: Thanks. Yep, I’m continuously amazed at what is not obvious.

Wayne Fischer • Quite right, Stuart, quite right – I could have. But, OTOH, I was taught that the first time you use an acronym, you should spell it out for the reader…not assume he knows…as a courtesy… 🙂

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Wayne: The HFMA Linkedin Group is not a bastion of process improvement or change. I tried to post the same topic there, but have yet to see it: got caught in their filter.

In the Linkedin ‘Healthcare Executives Network’ I did get one response, “Robert B. Shields • Is this common sense or “rocket science”? Seriously, I think this has great potential for strategic planning.”

The HME group, on the other hand, tends to have more thoughtful, insightful comments.

Stuart Singer • You got me on that one Wayne. It’s just that I assume that smart guys like you and Brian know everything already!!!!

I have to admit that this approach is not something that I’m grasping completely. That’s why I’d like to see if and how it is being applied by a hospital and how it has led to advantageous changes. I thought if anyone might know that, it would be the HFMA (not the discussion group) since they represent the financial element in healthcare.

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Well Wayne… Looks as though you have the potential for a ground breaking analysis and solution of a major fundamental problem with healthcare finance interfering with healthcare improvement.

Yep..I can see articles in several journals, speaking engagements, offers galore… Wine, Women, Song! You can sing, can’t you?

Ya just need to do your 6 month study.

Wayne Fischer • [Thanks, Brian, for cracking me up – LOL in my office! 🙂 And yes, I *do* sing – 12 years in our church choir, voice lessons going on 7 years! 🙂 ]

And you are right, soon’s I get to come up for air I’m gonna learn enough about Throughput Accounting (to be dangerous) to somehow incorporate it into my six-month pilot of Statit. After all, “value” in healthcare is more than just good outcomes…

Stuart Singer • Everyone wants to be in “show biz” Wayne stick to being a quantitative genius. Fixing the healthcare system has to take priority over winning American Idol!!!

Wayne Fischer • OK, OK, Brian – you’ve convinced me. 🙂

[ Now tell me the name of that d@#$ software! ]

Dennis McInerney • Hey gents,

The TLA’s (Three letter acronyms) are all over the place on this thread so I am going to plead ignorant on posting any solutions to Brian’s original question on TA. However, if you get a chance (maybe you already have read this), read “Profit Beyond Measure” by By H. Thomas Johnson and Anders Broms (ISBN-10: 1439124620,ISBN-13: 9781439124628). Here an accountant describes why GAAP and ABC promote as Douglas and you all describe/suggest as “anti-lean” accounting systems. This really is a huge issue for quality and operational improvement efforts.

Thanks for education on TA and TPA

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Thanks Dennis. You are aware though……That you’re preaching to the choir… 🙂

I’ve been harping on this topic for years. There’s a lot more that needs to be done with finance and hospitals, but this is one of the essential first steps. Once this is done, the dominoes will fall and some serious work will begin.

A rigorous study, such as we’ve been discussing, would force the issue. I may have been joking around, but I wasn’t jesting about the importance of it all.

Dennis McInerney • Hey Brian,

I don’t know how to preach and so far Wayne is the only one who can sing so does one singer make a choir:)

Yep like I said I cannot offer any solutions at this time, just another believer that our accounting systems have to evolve faster then the North pole melts…

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Amen brother..amen.

Dennis McInerney • Praying always helps, but may not fix our present day accounting systems:)

You burning the midnight oil Doc?

Seriously, an interim approach I have used to at least show in the current

accounting systems where we need to improve (invest resources) and act as

another scorecard is Cost of Poor Quality “buckets”.

The Wiki does a decent job describing this concept. If you are too

implement I would look to other sources (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cost_of_poor_quality

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cost_of_poor_quality> )

If you are familar with this concept then again, I have provided no value

just preaching:)

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • RE: COPQ

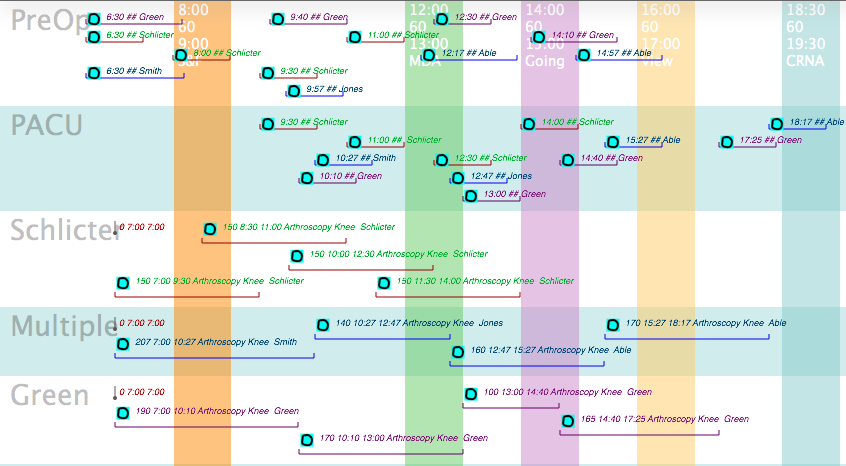

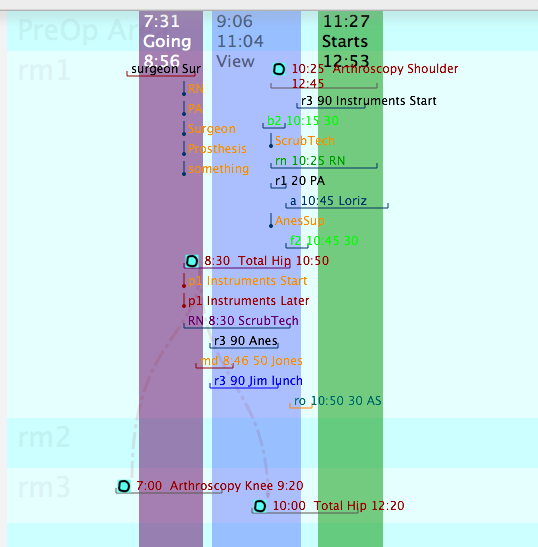

I’ve done something similar with anesthesia in the OR. I refer to it as ‘finessing’ cases which includes decreasing time, materials, depth of anesthesia, risk and integrating all that into the existing flow of cases. When done well, people may not realize what occurred–just that it was a really good day. Never thought in terms of ‘buckets’ though.

The finessing made going to work fun and challenging. It incorporates a lot of information and skills outside of classic medicine.

Yep, it’s late; time to call it a day. Thanks for the links, Dennis.

Douglas Dame • Brian or anyone:

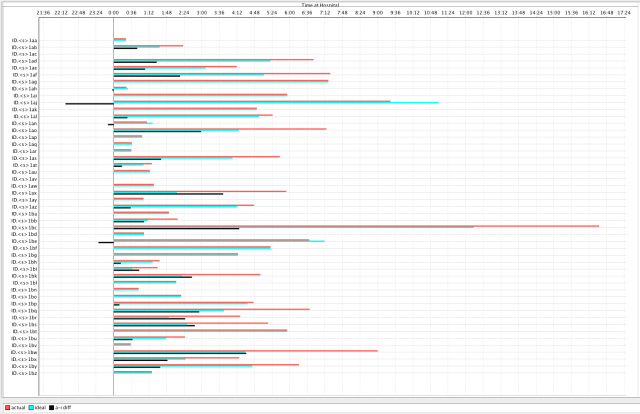

I don’t kmnow much about Throughput Accounting, but it seems (to me) to be intrinsically wrapped around a (comprehensive and exhaustive) process flow map (my words) for the area under study.

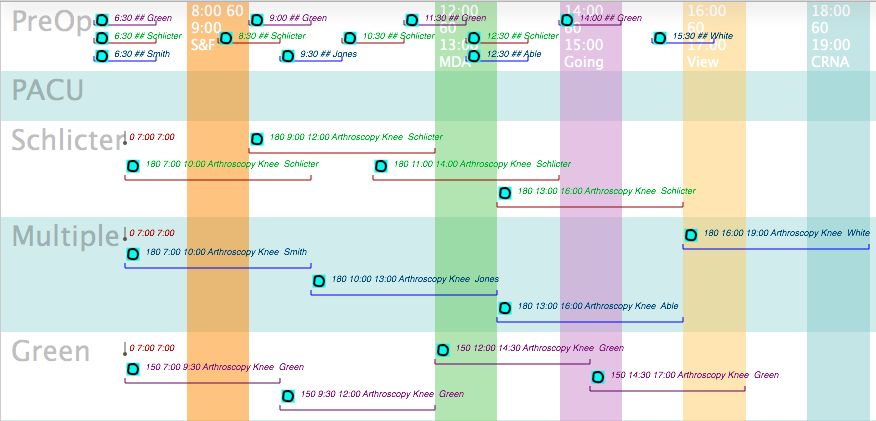

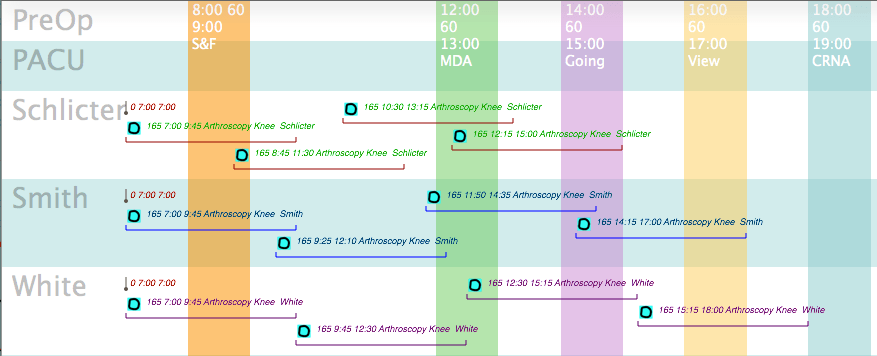

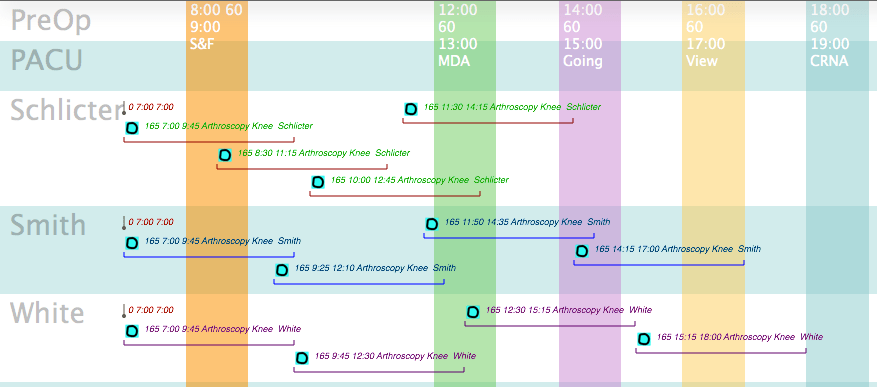

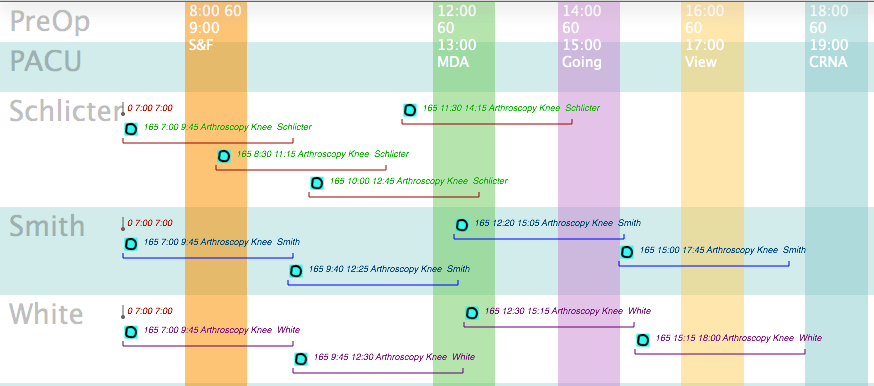

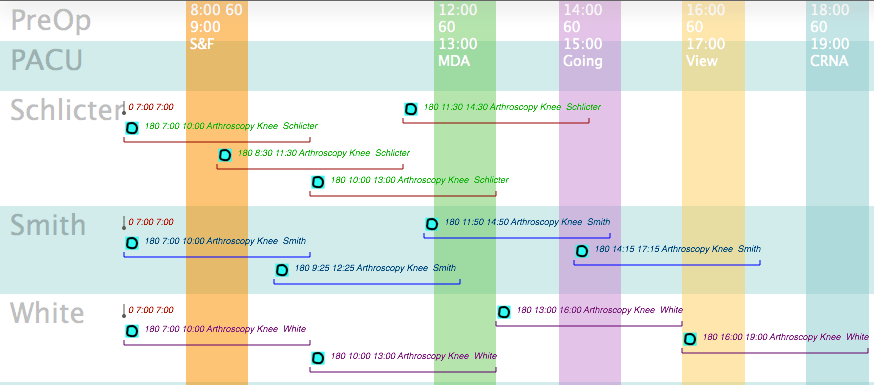

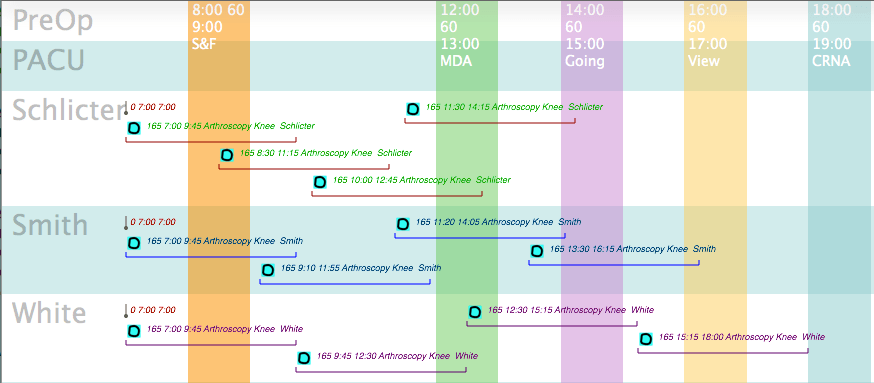

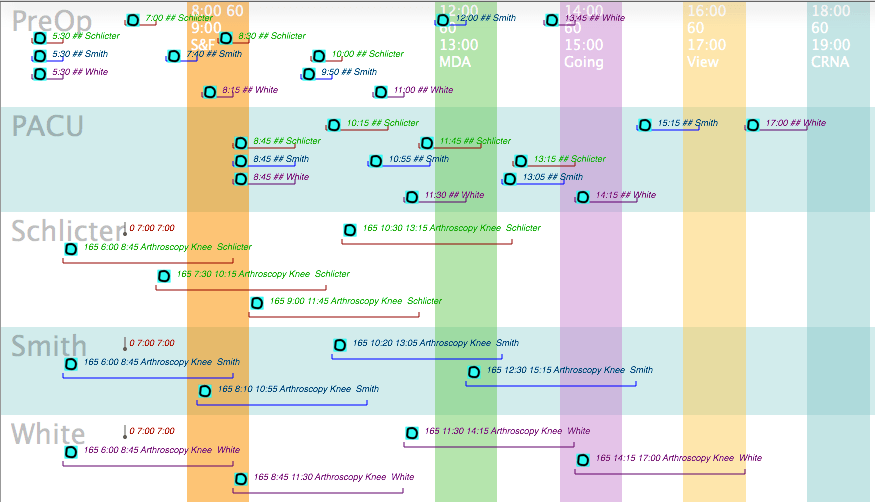

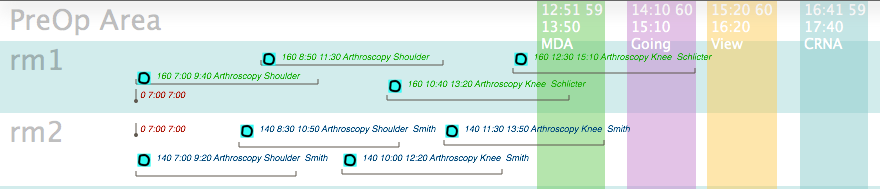

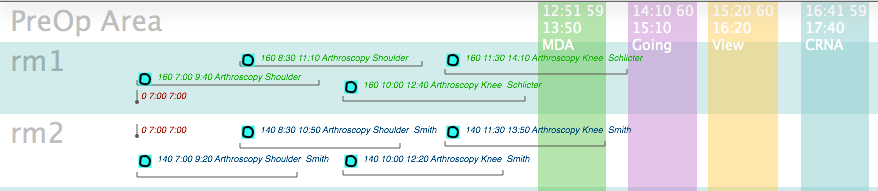

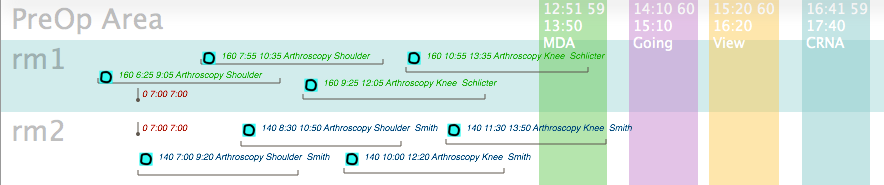

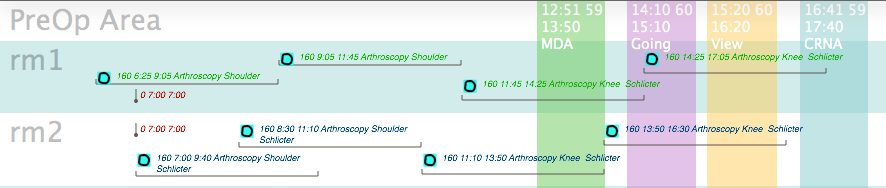

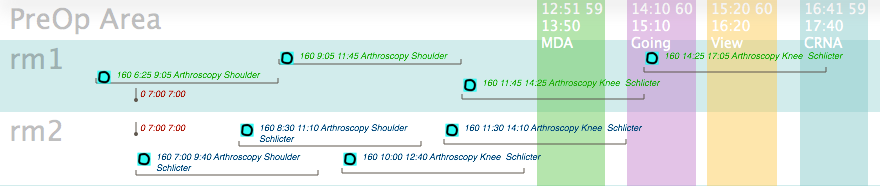

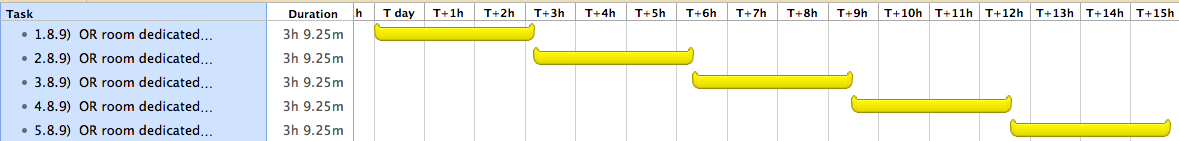

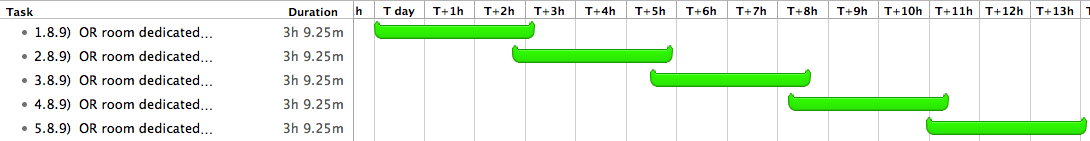

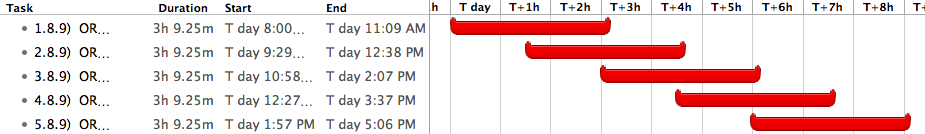

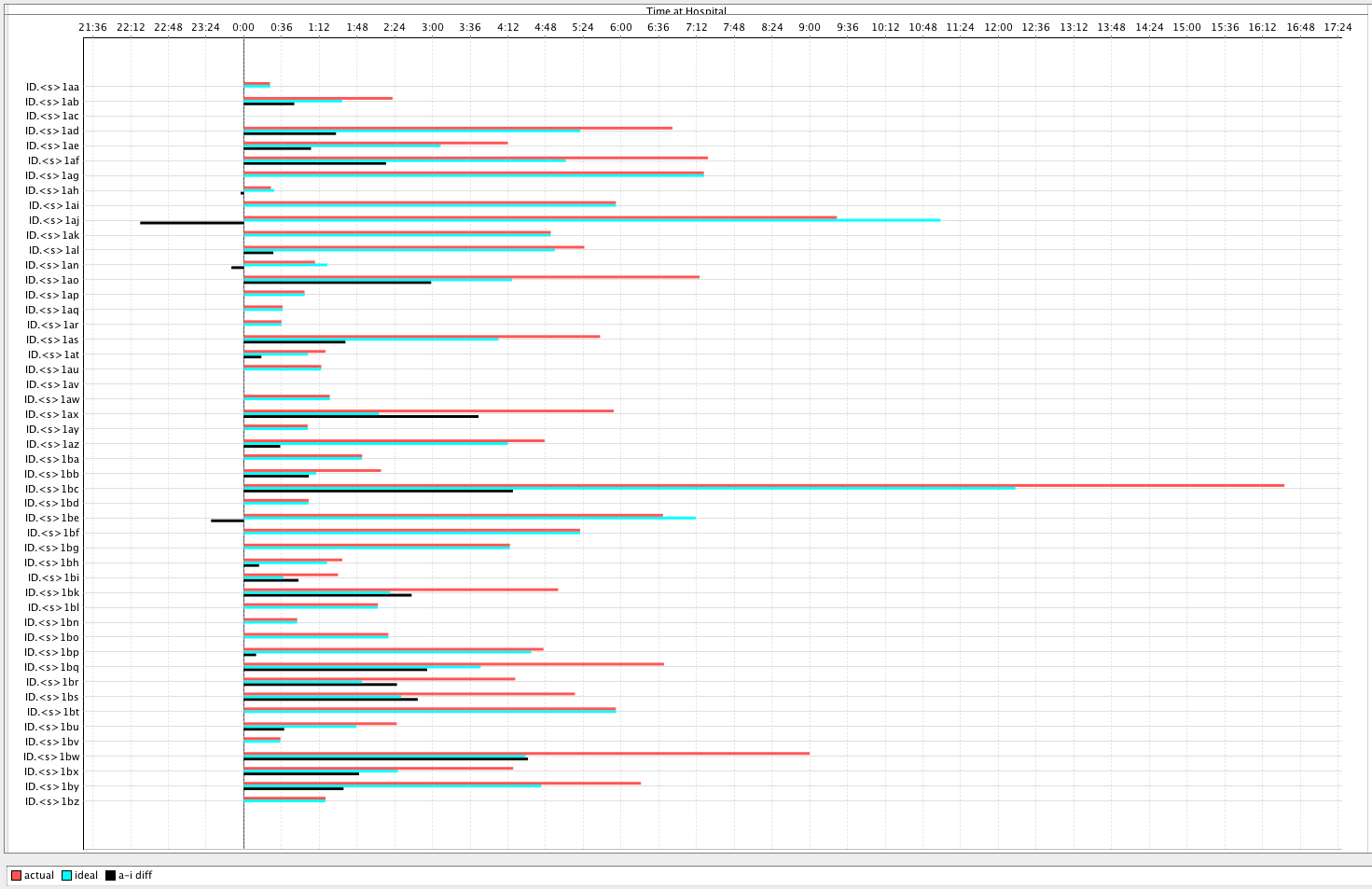

The only healthcare examples I’ve casually run across have been in single-specialty outpatient clinics, or in Brian’s case, apparently for the O.R. suite. The later is definitely not my area of expertise, but to my naive mind, the patient flow is fairly regimented and straight-forward, if the scope of analysis is from the patients’ arrival at the pre-surg waiting room until the patients leave the recovery area.

So my questions are:

(1) Is my very skimpy description basically correct?

(2) How do you handle “messy” flows where a wide diversity of patients arrive, and the diagnostic and treatment plans are totally unknown?

(3) Does TA “scale-up” to an entire, complex hospital?

(4) Assuming you can’t create process maps & data capture mechanisms for every nook & corner of a hospital in a short time period, how do you phase in TA, and what do you do for cost accounting for the other areas in the interim?

(5) Are there any U.S. hospitals that are examples of a complete TA implementation? (With all due regard to other places, Peter Drucker once commented that the American academic hospital was the most complex business on earth, and it’s gotten x-notches more difficult since then. So I’m not confident we should assume that successful experiences in other countries can be extrapolated to the U.S.)

(6) Brian: You’re obviously unwilling to name the vendor of your software. Am I correct in inferring from what you wrote that you did NOT buy/license a purpose-built “Throughput Accounting” application ?

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Hi Doug-

Can’t spend a lot of time on this now, but briefly:

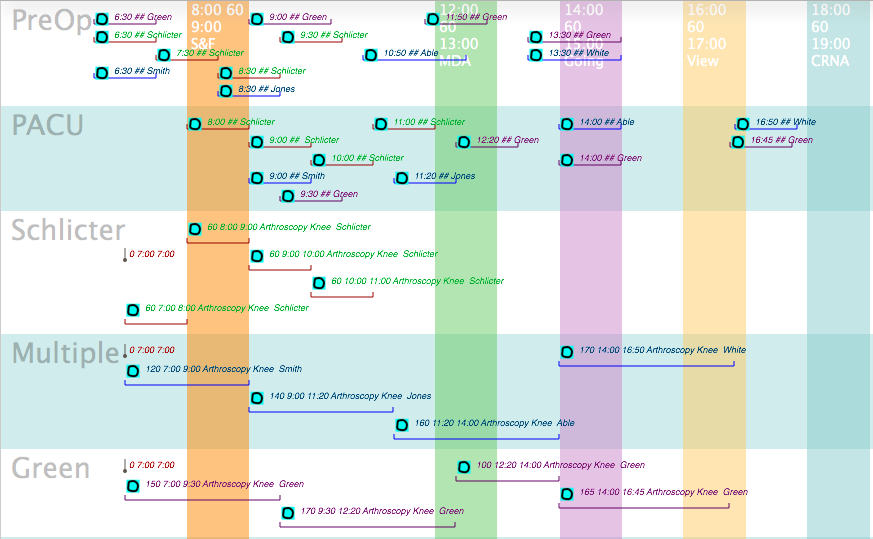

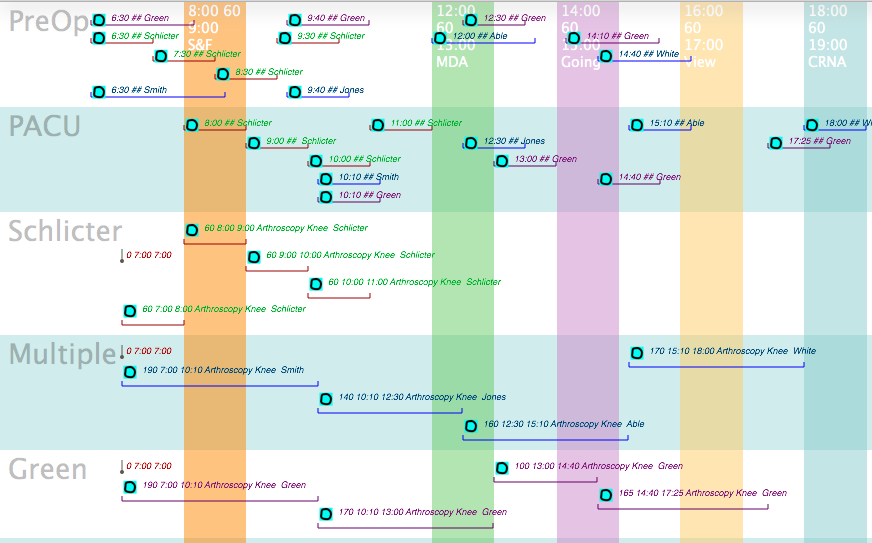

(1)&(2):Pt flow in the OR is chaotic, but the chaos usually comes from unknown arrival and departure times of ‘known’ types of cases. The ER has many unknown cases, but the procedures and resources that deal with them are known and can be optimally setup by using TOC (Theory of Constraints).

(3) & (4): I believe that it is possible to run both accounting techniques simultaneously. Initiating TPA could be done a department at a time to help with decision making. What Wayne and I were discussing is a way to convince the accounting department to look at the data so that when trying to help manage (Throughput Accounting is a dialect of managerial accounting) processes for profit they don’t make suggestions that are contrary to those experience and knowledge of those clinically involved. Ideally, they should be able to give useful answers to questions the clinicians have involving decreasing costs or increasing revenue. How far one scales up is dependent on how well the leaders understand TOC (Theory of Constraints).

(5):I will agree that scheduling in a hospital (my experience is with ORs) is an order of magnitude faster and complex than many other industries. There are issues that you rarely have to deal with elsewhere, too.

Back in 1998 I wandered over to Jim Womack’s office in Brookline (Boston) and had a discussion with him about Lean Management. He’d recently helped try to shorten the wait times at a local hospital ER, but was quite frustrated due to the complex politics involved.

(6) (a)Making an accounting package a “Throughput Accounting” application involves setting the accounts and other fields up in an appropriate manner to do it. Your normal run-of-the-mill bookkeeper would not have the expertise in accounting, nor the expertise in the clinical situation to do it correctly. (b) I did not tell Wayne the name because he would go crazy trying to set it up, and he would curse me for it afterward 🙂

Paul Walley • i would be uncomfortable using just TA in an organization – there are plenty of ways in which other costing methods can be used effectively for some performance measurement and decision-making purposes.

There is one imperative: we must stop existing systems from encouraging every part of each system to work as close to 100% utilization as possible. We need to ensure that non-bottlenecks are allowed to work to the same pace as the bottleneck.

There is some evidence that yield management (IT) systems increase output at the expense of quality (mortality). The reason is that the partial implementations of throughput optimization factor only the capacities of the fixed assets – inevitably beds and OR in most cases. This can result in full facilities but staff too busy to keep everyone alive (staff being the true constraint).

Hence I would be nervous about any partial implementation of TOC/TA. In my opinion we have to be careful not to assume that OR throughput is the problem when there may be other constraints in the system.

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Hi Paul- The suggestion for Wayne to run an experiment using different accounting systems (at least reports) with different departments is an attempt to choose the most appropriate accounting system that supports the ‘goals’ of that department. Those goals could include morbidity, mortality, etc.

As is usually stated in the TOC literature…first you choose your constraint (which can have boundaries itself) depending on what you are trying to achieve (goals/personal interest).

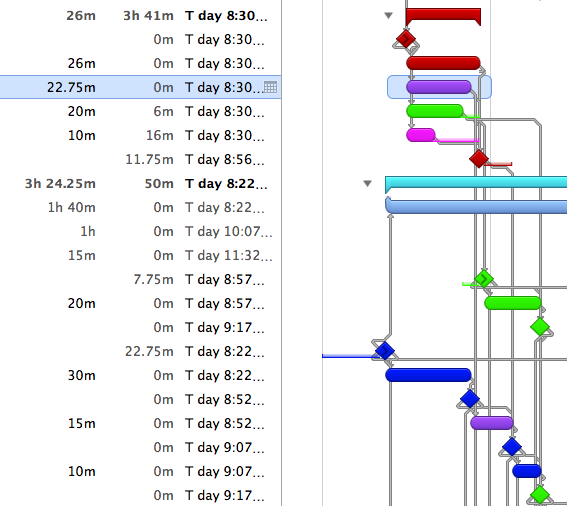

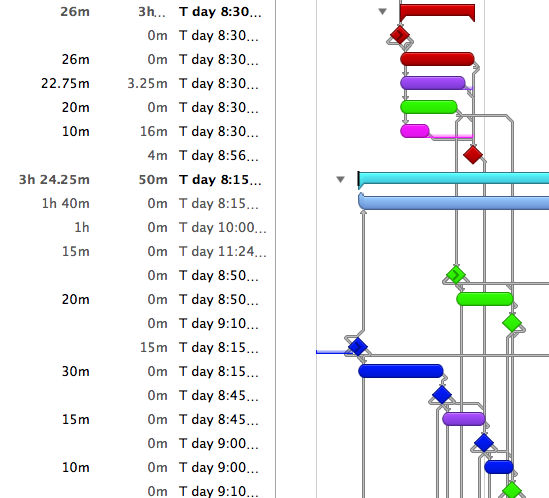

I’ve gone into great depth on my weblog about the conflicting constraints in an OR due to the different agents involved, most notably surgeons, anesthesiologists, and hospital. I’ve shown how to modify those constraints on the fly when resources vary.

I’ve also shown that the net economic gain in the OR can be shared by all, and that nurses and anesthesiologist can have more time (decreased risk) for the patient while the surgeon (who is normally the one pushing for faster turnovers) can modify his speed to his liking (no external pressure — only his own).

For the company (hospital) as a whole, TOC will determine which specialties, illnesses, patient demographic and therapies will be most supported with existing resources…or whether new resources should be acquired to change the constraint and strategy.

The individual departments would use TOC (and accounting) to optimize their constraints (with boundaries such as no mortality or happiness for employees). When getting down to this level of implementation, knowledge of the processes involved is essential to adapting (modifying) the accounting system to support the outcomes.

Improvements in the processes (recognized and supported by appropriate accounting) at this lower level will affect the strategy at the top level of the company… and the constraints at the top level of the company. It’s symbiotic and iterative.

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Someone brought to my attention that the exact definition of symbiotic has been argued for years. Symbiotic, in my usage, refers to an interdependent relationship—not specifying whether mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasitic.

Ideally, accounting and clinical practice should be mutualistic.

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Google ‘commensalistic’; it’s used in lieu of commensal many places. One of my references for checking the meaning (after my prior chastisement) was ‘symbiosis’ in Wikipedia where it’s spelled ‘-istic’.

We’re referring to commensalism. ‘Commensal’ sounds better, but when comparing the three forms, ‘mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasitic’ rolls off the tongue in a fantastic flurry of ‘istics’.

Robert Gordon • “Ideally, accounting and clinical practice should be mutualistic.”

Yes, I suppose… at least if we stipulate that, in cases ideally considered, accounting benefits clinicians. In real organizations, accounting is more readily seen by analogy as functioning parasitically. This is especially so when you consider that these terms have to do with species reproductive fitness in evolutionary dynamics, and the capacity for staff positions to enjoy much higher reproductive rates, because of their unequally advantageous sharing in the return from effort/risk at the frontline.

But I am skeptical of the value of such analogies in organizational improvement. Perhaps, as an MD, biological metaphors are more attractive.

If you are in the mood for some complex thinking about inter-departmental structures and interactivity, I recommend the very different model offered by Chester Barnard, The Functions of the Executive (1939). Pay close attention to his definitions of efficiency and effectiveness as well as his functional (not ontological) model of the organization. [It also helps to read his Appendix on perception before beginning Chapter 2.] Perhaps the “hardest” book I have ever read.

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Just thought I’d expand on some thoughts about Acitivity Based Costing (ABC) vs Thoughput Accounting (TPA): [not quite sure how TDABC is handled]

Idea of TOC:

Optimize the application of resources (with many abilities) to any or all activities to achieve a goal.

=(resource x activity) cross product

Parameters of throughput goal:

(1) Defined goal/purpose/gain

(2) Time period (this month, this year, this life, life of planet) of this goal

(3) Risk your willing to take of running out of specific resources during that time period (some resource shortages merely cause delays, others such as cash or oxygen could cause the end)

This makes an accounting system a little more complicated. The “resource x activity” refers to the cross product of the two. That means that you need to keep track of both at the same time if you’re trying to improve things.

So, in my view, Activity Based Accounting is a simplified view of TPA. The parameter 1,2,and 3 are essential to TOC and hence TPA. You might also assume that parameters 2 and 3 can include the concepts of real options (hellaciously branching decision trees) that require a good bit of strategizing.

Then again, isn’t top management supposed to be ‘strategizing’ all the time? If so, then TPA would be the act of carrying the strategy down to the process level on an informed basis (sure..let administration run the machines:).

It looks as though true TPA would require more coordination and transfer of information from the people actually designing and doing the processes and the administration strategizers. ABC would not require such coordination of effort, and might not consider parameter 1,2, and 3 adequately (inadequate strategizing).

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • continuing…

If the goal of TOC is to maximize cash flow, then TPA should correlate with the cash flow in the company.

However, it’s conceivable the the TOC goal is something other than maximizing cash flow (charity?, or ::ROFL:: not-for profit hospital!), in which case you’ll still have to maintain sufficient cash flow to stay in business (unless you’re the VA).

Often it seems that current hospital cost accounting does not appear to emphasize cash flow…nor charity…nor long term patient health. I’m not sure what the strategy is…nor if the strategy is frequently reevaluated.

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • continuing…

The goal in TOC would determine the clumping of actions into activities. Different goals can easily imply a different set of actions that lead to specific activities and the the measured TPA activity expenses and revenues would change accordingly.

This means that a ‘randomly’ set up definition of activities for ABC might, or might not, jive with the TPA system. Same goals, though, could cause ABC and TPA to be indistinguishable in effect.

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Paul- So I agree with you that a partial implementation of TOC/TA would be less than optimal for the hospital as a whole.

But…there will be politics in that the the GI department will have a goal that is more aligned with the gastroenterologist, the pulmonology department will have a goal more aligned with that of the pulmonologist, etc.

The goal may still be cash flow…but whose cash flow?

Throughput accounting could be used to quantify by cash flow how far the goals of a particular department veer from those of the hospital, and what or who is the cause. Negotiations could ensue: possible recognition of the amount of loss in the potential total economic return, and ways to indirectly share income.

An example is that of paying surgeons to cover surgical call. Ten years ago I remember a hospital claiming (in the newspaper) that a group of neurosurgeons was holding it hostage by demanding to be reimbursed for coverage (the group of three covered three hospitals every night with no reimbursement). Nowadays, compensation for call is the norm.

Another example is guaranteed income for anesthesiologists who wander all over the hospital expediting sedations, intubations, epidurals, doing medicaid/medicare cases etc. for which they often are poorly directly reimbursed, but for which the hospital makes lots of money (eventually).

Robert Gordon • Brian,

This last string of your comments has brought a whole new ray of enlightenment into the dusty loft of my mind. As we have discussed elsewhere, stereotypical healthcare activity essentially value-optimizes intra-operative decision making above the reduction of process variability. You have here made me remember and better understand something I was working on a couple of years ago, namely, the fact that the main value killer (“waste” for Lean) occurs in transitions or hand-offs during hospital care, both within and among disciplinary siloes. [I believe you are well aware that this process “articulation” is the focus of research and experiments in process modelling, DEM.] But the fact that transitions are a problem in hospital care probably has a homolog in the inescapable variability of healthcare processes. You say TOC (but QI methodologies in general) try to aggregate “actions into activities”. That is because of the all-unifying Goal. But in health/hospital care, there is no “goal” in this sense. You could say that the “Goal” of healthcare (health) is transcendent and equally present to every action, but that really just shows that “goal” is not the right concept. Ooo! it is all coming together! Thanks.

Brian Gregory, MD, MBA • Robert,

LOL…Glad I could help! Please keep my analyses straight, though. I was using this conversation as a sounding board…cause it would have looked silly had I been talking to the wall. The wall does a bad job of critiquing.

And, when you do get the ‘Unified Theory of Healthcare’ all worked out—please share it. 🙂